Sunday Reads #152: How a 2015 decision by Twitter resulted in its current fiasco.

The surprising power of path dependence.

Hey there!

For folks who’ve joined over the last few days, sharing a couple of links that you might like:

Step by step, ferociously - looking back at 2021.

On to this week’s newsletter.

I’ve been surprisingly quiet about Twitter these last few months. So let’s fix that.

I won't lie, the Elon Musk - Twitter drama has been a lot of fun to watch.

Elon buys some Twitter stock. Twitter offers him a board seat. He says no, he'd rather be a passive investor. Then he mounts a takeover bid. Twitter creates a poison pill to prevent a takeover. Twitter then approves the takeover anyway. And then Elon says "No, I don't want to buy you any more". Then he says he's still committed to the acquisition. Then he says, “brb, counting spam bots.”

It's comical for us outsiders. But I feel sorry for the disgruntled employees at Twitter. You can only submit your resignation and then rescind it so many times, before Outlook disables your Recall button.

I guess we'll see what happens next. Watch this space.

Actually, don't watch this space. For I have no intention of reporting on this tragicomedy.

Instead, let's talk about something that happened at Twitter 7 years ago. Something that was pivotal in creating the situation Twitter finds itself in today.

A billionaire tries to take over Twitter, 2015 edition.

@rabble has an excellent thread on Twitter about how Twitter first became vulnerable.

Twitter used to be an open platform. Many players were building applications on top of Twitter, to interact with the feed.

But then, a billionaire (Bill Gross) tried to buy every third-party Twitter tool, so that he could create a Twitter clone.

Twitter had a choice on how to protect itself:

Block / throttle all the APIs so third-party Twitter tools would be severely handicapped.

Come clean to the community. Make the developers (who all loved building on twitter) partners in protecting it.

Twitter chose the first option. And in one fell swoop, converted Twitter from an open commons to a walled garden.

Fast forward 7 years.

The product has stagnated. The user base has stagnated. Everyone is incredibly frustrated.

Twitter had the chance to become an infrastructure protocol like email. It had the chance to become the world's town square.

It had the opportunity to unleash third-party creativity on its platform. Which it could then copy to make Twitter itself stronger - like how Gmail has evolved.

Instead, it's a bad social network. Stagnating in the shadow of Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok.

Such a massive opportunity. And Twitter blew it.

It's fascinating how pivotal a role path dependence has played, in how Twitter looks today.

A different response to 2015's hostile takeover bid, and today's hostile takeover might never have come about.

There are three lessons to draw out of this Twitter story. One for large companies, one for startups, and one for you and me as individuals.

Let's go with the first:

Lesson for big companies: Don't f**k with the culture.

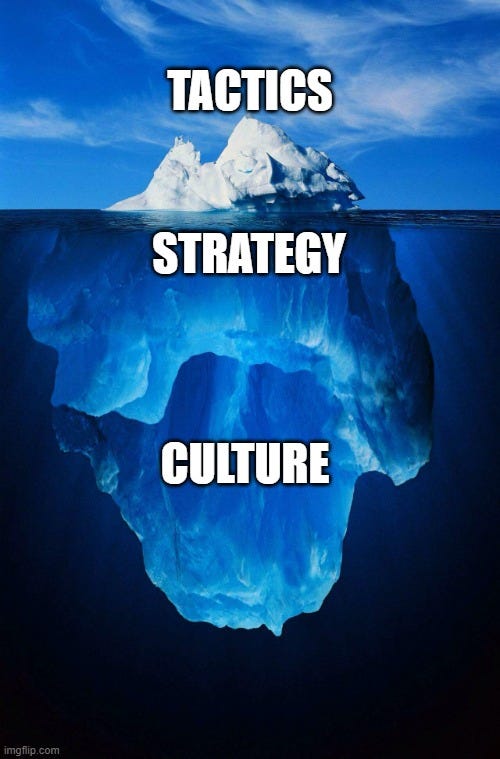

As they say, Culture eats Strategy eats Tactics.

I've written about this before. If only you could just copy Amazon's tactics ("let's start writing 6-page memos") and snap your fingers. And magic! You're a billion dollar company.

Facebook also has a culture code. There's "move fast and break things", but there's also another unsaid code. Survival is Everything.

Facebook will fight violently to survive. It will vanquish competitors (remember Google Delenda est?) or buy them out (Instagram, WhatsApp). And if they refuse to be bought, it’ll copy them shamelessly (Snap).

This is not an endorsement of Facebook's culture. It's just an observation: the most valuable thing you have as a company is your culture. What employees do when the CEO is not in the room.

Don't f**k it up.

You remember that iceberg photo, which shows how 80% of an iceberg is under water and not visible?

That's true about companies too.

You might see tactics like 6-page memos and two pizza teams. But under that is a strategy.

You might see a strategy of product-led growth. But underneath that is a culture, a set of beliefs.

And this invisible, intangible, ineffable culture, is the most powerful asset you have as a company.

Lesson for startups: Exploit big companies' path dependence.

Twitter was a slave of its history. It made a decision a few years ago, which forked it a completely different path.

Twitter's history constrained its future.

With that framing, you start seeing other examples of path dependence.

Kodak, the photography behemoth of the 20th century, couldn't cope with the digital camera era, and had to shut down.

As Hamilton Helmer says in his excellent book 7 Powers:

Pundits have chided Kodak for poor management, lack of vision and organizational inertia for standing by, while digital cameras came and made them extinct.

In fact Kodak was fully aware of its eventual fate and spent lavishly to explore survival options, but digital photography simply was not an attractive business opportunity for the company.

Kodak's business model was built on its power in film. It was not a camera company. The technological frontier had moved and consumers were better off, but Kodak was not.

Nokia is another great example. Stephen Elop's Burning Platform memo in 2011 shows the immense frustration of being a slave of history.

The first iPhone shipped in 2007 and we still don't have a product that is close to their experience. Android came on the screen just over two years ago, and this week they took a leadership position in smartphone volumes. Unbelievable.

When competitors poured flames on our market share, what happened at Nokia? We fell behind. We missed big trends and we lost time. At that time, we thought we were making the right decisions, but with the benefit of hindsight, we now find ourselves years behind.

There are several more examples, but lest I lose you, let's come back to the question in your mind: OK, so what's the lesson for startups?

It's this: Understand your competitors' strategic constraints. And counter-position vs. them.

Adopt a model which the incumbent cannot mimic because of the collateral damage to their existing business.

Helmer describes this approach in great detail in his book. He uses the example of Vanguard's low-cost, no-load index funds.

Vanguard's approach was head-and-shoulders better than the existing options available to customers. As Helmer says:

Vanguard's business model resulted in substantially lower costs, which then translated into superior product deliverables, such as higher average net returns.

Due to their business structure of returning profits to fund holders, they realize value from market share gain, rather than ramping up differential profit margins.

Why then did incumbents like Fidelity not copy it?

They were bigger, they were entrenched. They were sitting on cash. And most important, they had distribution.

Why could they not just copy Vanguard and destroy it?

Back to Helmer:

The barrier, simply put, is Collateral Damage.

In the Vanguard case, Fidelity looked at the highly attractive active management franchise and concluded that the new passive funds' more modest returns would likely have failed to offset the damage done by migration from the flagship products.

Fidelity could have gotten into the space and challenged Vanguard. However, the impact of entry into passive funds on the remaining base business of active funds would have been subtractive.

Fidelity had no choice but to sit back and watch, helplessly, as Vanguard ate its lunch.

Play your cards right, and your competitors will watch you eat their lunch too.

Lesson for you and me: Harnessing path dependence in our lives.

Arno Rafael Minkinnen, a Finnish-American photographer, has a great allegory:

The Helsinki Bus Station: let me describe what happens there.

Some two-dozen platforms are laid out in a square at the heart of the city. At the head of each platform is a sign posting the numbers of the buses that leave from that particular platform. The bus numbers might read as follows: 21, 71, 58, 33, and 19.

Each bus takes the same route out of the city for a least a kilometer stopping at bus stop intervals along the way where the same numbers are again repeated: 21, 71, 58, 33, and 19.

Now let’s say, again metaphorically speaking, that each bus stop represents one year in the life of a photographer, meaning the third bus stop would represent three years of photographic activity.

Ok, so you have been working for three years making platinum studies of nudes. Call it bus #21.

You take those three years of work on the nude to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the curator asks if you are familiar with the nudes of Irving Penn. His bus, 71, was on the same line. Or you take them to a gallery in Paris and are reminded to check out Bill Brandt, bus 58, and so on.

Shocked, you realize that what you have been doing for three years others have already done.

So you hop off the bus, grab a cab (because life is short) and head straight back to the bus station looking for another platform.

This time you are going to make 8x10 view camera color snapshots of people lying on the beach from a cherry picker crane.

You spend three years at it and three grand and produce a series of works that elicit the same comment: haven’t you seen the work of Richard Misrach? Or, if they are steamy black and white 8x10 camera view of palm trees swaying off a beachfront, haven’t you seen the work of Sally Mann?

So once again, you get off the bus, grab the cab, race back and find a new platform. This goes on all your creative life, always showing new work, always being compared to others.

What do you do?

Arno continues:

What to do?

It’s simple. Stay on the bus. Stay on the f*cking bus.

Why, because if you do, in time you will begin to see a difference.

The buses that move out of Helsinki stay on the same line but only for a while, maybe a kilometer or two. Then they begin to separate, each number heading off to its own unique destination. Bus 33 suddenly goes north, bus 19 southwest.

For a time maybe 21 and 71 dovetail one another but soon they split off as well, Irving Penn is headed elsewhere.

It’s the separation that makes all the difference, and once you start to see that difference in your work from the work you so admire (that’s why you chose that platform after all), it’s time to look for your breakthrough.

Your path is what makes you unique. It's what creates your "personal monopoly" - what you're better at than anyone else in the world.

So stay your course.

Stay on the bus.

Hi, I’m Jitha. Every Sunday I share ONE key learning from my work in business development and with startups; and ONE (or more) golden nuggets. Subscribe (if you haven’t) and try it out for free 👇

Keep calm and buy the dip? (Not financial advice).

I was going to write a little today about the bloodbath in crypto (I hope you didn't lose much money on Terra and Luna!). But today's letter is already getting long, so will do that next week (watch out for that!).

In the meantime, let's talk about the crash that's happening across markets right now. Crypto, stocks, everywhere.

Frank Rotman (@fintechjunkie on twitter) wrote a great thread during a dip in the market back in Jan.

It's worth re-reading now.

He makes an excellent point.

During a crash, there's a high level of FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt). People start to panic. Fear dominates headspace.

The reason for the panic is that you can see the prices in real time. Mr. Market is telling you the price every second.

Every second, he's telling you what your ownership is worth, if you were to exchange your asset for dollars.

But here's the thing: If you're not going to sell the asset now, then the price doesn't matter. You still own the asset and no one can take that away from you.

Rotman calls this "Ownership stability".

The crypto world likes to remind “no coiners” that 1 BTC = 1 BTC and 1 ETH = 1 ETH.

It took me a while to understand this perspective, but I’ve come to the conclusion that this truism has very broad application if understood at the atomic level.

The first principle that guides this truism is that the ABSOLUTE OWNERSHIP of an asset is fixed while the RELATIVE VALUE of an asset fluctuates based on market sentiment about the asset.

Internalize that nobody can take away something that you’ve bought. You own it. Full stop.

If you don’t want to sell your asset now, then the exchange rate of “your asset to fiat currency” doesn’t matter.

What matters is the quality of the underlying asset.

And what matters even more is contextualizing what the asset is likely to be worth when you plan on selling it.

If you're able to wait for the markets to stabilize (or even for a bull market) to sell, then today's price doesn't matter. What matters is your confidence in the asset.

Remember what Ben Graham (Warren Buffett's teacher) said:

In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run it is a weighing machine.

In summary, this dog has got it right.

This blew my mind 🤯

OpenAI's DALL-E is 🔥. I had goosebumps watching this.

Watch with SOUND ON.

"Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."

That’s it for this week. Hope you enjoyed it, and are staying safe, healthy and sane.

I’ll see you next week.

Jitha