Sunday Reads #150: The #1 mistake we're all making.

And how fixing it helped a startup get a $3.2Bn exit.

Hey there!

Glad to be back here.

Hope you’re keeping healthy and sane, wherever you are.

This week, let’s talk about the #1 mistake we’re all making. Whether in business or in our careers.

1. You're pricing too low. Each and everyone of you.

Segment is one of the big SaaS successes of the 2010s. It got acquired by Twilio for USD 3.2 billion.

I love this origin story from the founder Peter Reinhardt.

This story makes me want to scream "Raise Prices!!" from the rooftops. But it also highlights three important principles:

A: The right framing can bend reality.

There's a saying among negotiators: If I set the terms and you set the price, I win.

If you control the terms of a debate, you're almost always also controlling the outcome of the debate.

But the power of framing is not only about negotiation tactics. With a different framing, your own expectation can change completely!

Listen to Peter explain why he was pricing too low in the first place:

The underlying challenge was two-fold:

(1) analytics.js was an open source library and we came from the open source mindset, so our anchor was $0,

(2) we were all fresh out of college, had a few hundred bucks to our names, and had never sold anything.

He was looking at it from a framing that made any price seem too high. The default in open source is free!

It took an external advisor to grab his shoulders and shake him violently, to transform his frame:

So we hired @Mitch_Morando as our sales advisor, and he immediately blew our minds: “This is an enterprise software product. You’re charging $120/yr? You should be charging $120,000/yr.”

That was the first 🤯 moment for Peter. There were many more such moments in the next few months.

We sat down with [a customer] Nat and his team. All I remember is the end of the conversation where he asked what our pricing was. I said “$120,000 a year” and turned a deep, deep red.

Nat very, very graciously replied that he saw the value in $12k/yr. I pushed for $18k/yr and he agreed.

I was completely shocked. 150x higher price than what we thought was reasonable before. And Nat had explained how he valued the product, which we could reference next time.

From there, I was sold that we needed to raise prices to pressure test the real value we were delivering.

The next customer signed at $24k/yr. Then $35k. Then $48k. Then $105k. And then $240k. All in just 6 months.

I can see why this was an earthquake moment for Peter. I get surprised every time this happens.

I still remember - vividly - going into a big partnership meeting for my startup in 2014.

We were discussing a partnership with a big loyalty rewards company, to bring its users to my product. This partnership would be a game-changer for my company. It would eventually catapult us from 20K users to 200K users.

But my co-founder and I didn't know this yet.

Still, we went into the revenue-share negotiation ready to accept 80-20. i.e., they take 80% of the revenue the partnership generated. (actually we'd have accepted 90-10 🤫).

I started with the usual "So we'll do a 50-50 rev-share right?".

And they said yes.

What an anticlimactic moment! But also a life-changing moment. Not only for my startup.

I could never see the world the same way again.

Tactical question: How to frame things right?

Simple rule: Don't price based on features or inputs. Price based on benefits and outputs.

❌ "Let's charge 10K / month because that's our server cost".

✅ "Let's charge $100K / month because the client will save at least that much."

B: Closed mouths don't get fed.

Shaan Puri has a great thread about asking for a raise. It applies to raising prices too.

You don't get what you don't ask for.

Unless you've tested the ceiling (and you know you haven't), you're pricing too low.

Marc Andreessen has another great analogy - don't be "too hungry to eat".

From Where to Go After Product-Market Fit:

The other big missing variable in all of this is pricing. I’ve talked in public about this before. What I don’t hear from companies is, “Oh, we don’t think we have a moat.” What I hear from companies is, “Oh, we have an awesome moat, and we’re still going to price our product cheap, because we think that’s somehow going to maximize our business.” I’m always urging founders to raise prices, raise prices, raise prices.

And from his podcast with Tim Ferriss in 2016:

The number one thing – just the theme and we see it everywhere – the number one theme that our companies have when they are really struggling is they are not charging enough for their product.

It has become absolutely conventional wisdom in Silicon Valley that the way to succeed is to price your product as low as possible, under the theory that if it’s low-priced everybody can buy it and that’s how you get the volume.

And we just see over and over and over again people failing with that because they get in the problem we call too hungry to eat.

They don’t charge enough for their product to be able to afford the sales and marketing required to actually get anybody to buy it. And so they can’t afford to hire the sales rep to go sell the product. They can’t afford to buy the TV commercial, whatever it is. They cannot afford to go acquire the customers.

When you ask for the moon, sometimes you get it!

I had shared Kanye West's story in Sunday Reads #105.

He asked for the moon in his negotiation with Adidas, and got it.

Retained 100% of the Yeezy brand

15% wholesale royalties (Michael Jordan gets only 5% from Nike)

Yearly marketing fee

Today, Kanye earns more from his Yeezy line than Michael Jordan does from the Air Jordans. And he doesn’t even play sports!

Where there was Kanye, there was Bill Gates first. Any discussion on making outrageous demands has to mention Microsoft.

Microsoft got started on its journey to world dominance with one epic negotiation. A plucky 20-year old pushed IBM into a sweet, sweet deal. Read The agreement that catapulted Microsoft over IBM.

Now, you don't have to be Kanye or Bill Gates, or even Steve Jobs creating a reality distortion field.

Keith Ferrazzi, the author of Never Eat Alone, mentions an anecdote from his childhood:

His dad, a factory worker, went up to the CEO of his company (his boss's boss's boss's boss), and asked him for help in his son's education.

Miraculously, the CEO said yes and agreed to help! Two things happened in that instant:

(a) it set Keith on a path through prestigious schools; and

(b) it firmly planted in Keith's mind an eternal truth - "all you have to do is ask".

Sometimes the customer will lead the way.

Going back to Peter and Segment, something strange happened when they first started raising prices:

By trying to ask for higher prices, we got customers to explain what they really valued about the product, and articulate that value quantitatively back to us. Our pitch got massively better, and we finally understood what we were selling.

Read that again.

When you meet your customer, just name your price. And then shut up.

Shut up and wait.

Sometimes, the customer will explain to themselves (and to you, coz you don't have a clue either) why your price makes sense.

You won't understand what the hell happened. All you did was take a few deep breaths and muster some courage.

But your customer is imputing more value to your product, in front of your eyes! Only because you priced it higher!

C: Don't negotiate against yourself!

This last one seems like a rookie mistake. Oh ho ho, but we all do it.

"If I ask for $7000 per month, then the conversation will end right there. Let's start with $5000."

"Let's ask them for 50% revenue share". "Oh no, they'll never agree. They're such a big company." "OK then, let's ask for 30%"

At one level, this makes sense. You don't want the other guy walking away because you asked for something crazy.

But at another level, it makes no sense. No sense at all.

Both sides want something from the discussion. It's very rare that people will walk away without even discussing, if you're way off their anchor. And when they do walk away, it's likely because the two sides are too far away, and never the twain shall meet. A deal wouldn't have been possible anyway. Lucky you, you saved some time!

But more laughable, this is exactly the cognitive bias of anchoring that you read about. Letting the opposite side's first bid anchor you away from what you really want.

No, it's actually worse than that. Because in this case, the anchor is entirely imaginary. The client hasn't even met you yet!

As a friend of mine says, there's nothing wrong with imagining people's responses. But if you're going to imagine something that's not real, might as well imagine a response you like. Positive thinking and what not.

Now, I can see you shaking your head. "Hmm. Great stories. But I don't buy it. Kanye can make an outrageous demand and get away with it. But I'm no Kanye! If I come across as slimy, the deal's off!"

Well, lucky I left the best for last.

The cheat code for making crazy demands.

Here's the cheat code (hope I’m whispering loud enough): It's not crazy as long as you have one, at least one, piece of logic for it.

"A previous deal in this industry was done at this multiple".

"I need to make a profit of x%".

Sometimes the logic is positional - e.g., if you want 50% revenue share, you don't need more logic than that. "We agreed to share revenue, so it's 50:50 right?".

Now you're thinking, "OK, I get the logic of doing this. But I still would be extremely surprised if they'll accept my sky-high price".

Perfect. That's exactly where you need to be.

Ask for your best case scenario. You'll be surprised how often you get it.

[Footnote: You will, from time to time, see that first offer rejected (else it's not high enough). What do you do then? Well, that's why good negotiators prep for all scenarios].

Sidebar: How do you know when your price is high enough?

A couple of thumb rules:

From Rahul Chaudhary, the founder of Treebo:

If your sales team is not cribbing about your prices being too high, they are too low.

I prefer a stronger filter:

If 10%-20% of your customers aren't turned off by your pricing, you're pricing too low.

Further Reading: How an agency owner went from $500 per month to $7000 per month, by changing how he framed his offer:

2. Golden Nugget of the week.

xkcd has an unfailing ability to take a mind-blowing fact, and make it even more mind-blowing.

Oddly, this reminds me of our mortality and how ineffective our lives are, on the ultimate scale.

Your legacy doesn't matter. Your achievements don't matter. The memories you leave behind - don't matter.

You'll be lucky to be remembered by one person 100 years later.

All this, on a vanishingly small, pale blue dot.

So what to do?

Optimize for interestingness. Do things that are fun.

Obey the inscrutable exhortations of your soul. You'll die anyway.

3. This made me laugh out loud!

After that somber reflection, something funny.

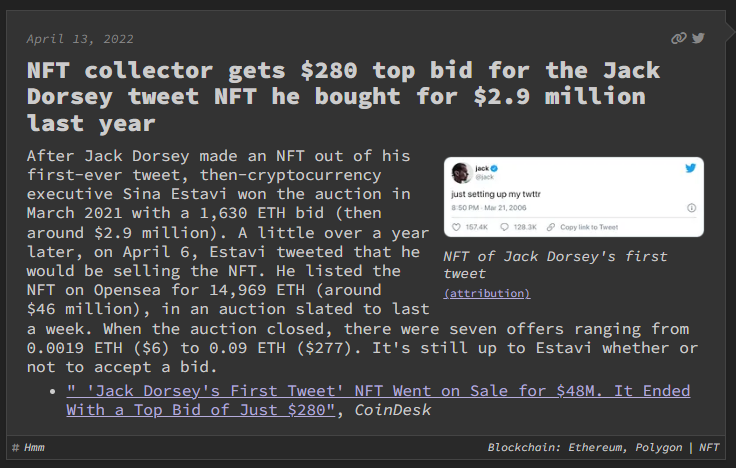

A good reminder: sometimes when you're scratching your head, thinking, "This makes no sense!", you're right.

Jokes aside, if any of you know Sina Estavi, please tell him not to sell to those bidders. They don't know the true value of Jack Dorsey's first tweet.

I'll pay him $281.

4. I hope you're able to sleep tonight.

This scared the bejesus out of me.

Read it to the end.

That’s it for this week.

With so many countries starting to open up, I’m tempted to believe the pandemic will soon be behind us.

I hope that’s true, and life can go back to normal at long last.

Until next week,

Jitha