Sunday Reads #161: The real story of Chernobyl OR The power and peril of pretty ideas.

Engineered to deceive.

Hey there!

Hope you had a great last couple of weeks! I’ve finally finished the move to my new house, and I’m excited to send out this week’s newsletter.

Today, let’s discuss the real story of Chernobyl. And why it is that we’ve never heard of it.

1. The Chernobyl Disaster, and the power of pretty ideas.

We all know the story of Chernobyl. It showed, in stark radioactive relief, what can go wrong with nuclear.

One hour after midnight on April 26, 1986, there was a massive surge of power at Chernobyl's Reactor 4. In an instant, there was a steam explosion, and a mere seconds later, another explosion, as flammable hydrogen gas caught fire.

A nuclear meltdown.

This is the story we know. Let me tell you a different one.

What really happened at Chernobyl.

Madi Hilly has written an illuminating thread on Chernobyl.

As she shares in her thread, here's the breakdown of deaths from Chernobyl:

3 deaths from the initial steam explosion

28 firefighter deaths from acute radiation syndrome

15 deaths from thyroid cancer in the 25 years after the accident

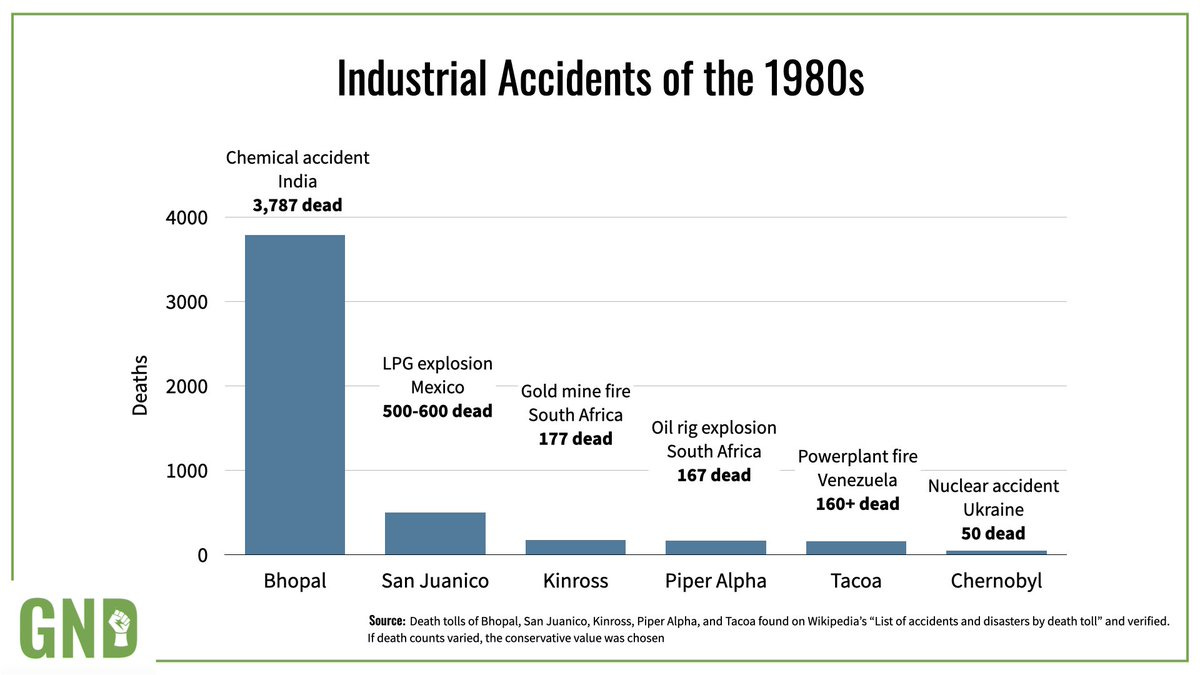

Now, even one death is a death too many. But have you heard of any of these other industrial accidents from the 1980s?

No one has heard of the San Juanico LPG explosion where 600 people died. Or of the oil rig explosion at Piper Alpha, where 170 people died.

But Chernobyl - with a couple of dozen deaths - set the nuclear power industry back by several decades.

In fact, there's more we don't know about the Chernobyl story:

Remember I said that the explosion was in Reactor 4? Well, reactors 1-3 continued functioning until 2000!

So, not only did the city NOT get vaporized, even the adjoining reactors continued working fine for 15 more years!

(They were decommissioned in 2000 under pressure from Europe. And against the will of the locals).

Moreover, there was no environmental impact from Chernobyl either.

I mean... there was, but not what you'd expect.

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is now the 3rd largest nature reserve in Europe.

What you expect: a post-apocalyptic Mad Max landscape. Everything killed by extreme radiation, except the two-headed toads.

What it actually is: a sanctuary for wildlife, no longer bothered by humans.

Why am I telling you all this?

There's a term in the debating world, called "Russell's Conjugation". It shows how you can use words to generate emotions, independent of the meaning of the words themselves.

In simpler terms, you can use loaded words to persuade the listener in the direction you want.

Some examples from Bertrand Russell, after whom it is named (via Wikipedia):

I am firm, you are obstinate, he is a pig-headed fool.

I am righteously indignant, you are annoyed, he is making a fuss over nothing.

I have reconsidered the matter, you have changed your mind, he has gone back on his word.

Eric Weinstein gives a few more examples in Edge.org:

The very same person will oppose a “death tax” while having supported an “estate tax” seconds earlier, even though these taxes are two descriptions of the exact same underlying object.

... such is the power of emotive conjugation that we are generally not even aware that we hold such contradictory opinions.

Thus “illegal aliens” and “undocumented immigrants” may be the same people, but the former label leads to calls for deportation while the latter one instantly causes many of us to consider amnesty programs and paths to citizenship.

The key learning is this:

Words don't just have meanings. They also have emotions attached to them.

And by choosing the right "synonym", you can incept a different idea in the listener's mind.

OK, but how is this relevant to Chernobyl?

"Nuclear meltdown" is a compelling visual metaphor. You think of a building dissolving into lava, making a town uninhabitable forever.

The reality, however, is far more humdrum.

But that's the point: once you have a simple, powerful idea, that's what spreads.

That's what journalists report, as they try to sensationalize with colorful language.

That's what you remember, as the image of a melting building plonks itself in your head. Soon, no one can dislodge it.

Facts cannot defeat a powerful, viral story.

So, to come to the point of the article. If there's one idea you take away, it's this:

Beware of pretty ideas.

Judah has a great article on Substack, titled What Do Your Ideas Want From You?.

Among other things, he talks about pretty ideas. Ideas that have just the right rhythm, just the right frame shifts, to trigger the believing center of your brain.

There are many ways to make ideas pretty. Listing three of them:

1. Simplicity:

In one of his old blog posts, Scott Adams talks about his writing process for God's Debris.

In that book, he describes a conversation between an omniscient being (God?) and a skeptical layperson.

As soon as he started writing this book, he faced an obstacle. Adams himself (despite his affect on Twitter) is not an omniscient being. Then how could he believably say what an all-knowing being would?

The solution he hit on (and quite successfully, judging by the book's acclaim) was this:

The omniscient being would say only simple things.

The simplest false explanation is far more believable than any complicated truth. Bonus points for using the words “Occam’s Razor”.

2. Analogies:

Analogies are especially powerful. They can completely change your frame of reference.

Scott Adams has a great 2016 article on this, called Bumper Sticker Thinking.

Quoting from the article:

People see patterns where there are none.

… Analogies are not a useful component of reason in the way most people believe they are. Just because something reminds you of something does not mean there is causation. Analogies are not about causation.

Analogies are great tools for explaining new things for the first time, and that is about all they are good for. For example, the game laser tag is like a real gunfight except with toy guns that have harmless lasers instead of bullets. That analogy saved me a lot of time explaining something new. But that is ALL it did.

The gunfight analogy has no predictive power beyond that. I can’t, for example, assume people will die playing laser tag because they die during real gun fights.

Analogies are for explaining, not predicting. Analogies are not part of logic or reason.

Analogies seem so persuasive.

And yet, they're - by definition! - not talking about the same thing at all.

3. Rhyme as reason:

This one is seriously stupid. Our brains are so dumb that just because something rhymes, we think it's true.

A delightfully titled paper, Birds of a feather flock conjointly? showed that people judged proverbs to be more accurate when they rhymed.

For instance, people were presented two versions of an proverb, as part of a survey:

"What sobriety conceals, alcohol reveals"

"What sobriety conceals, alcohol unmasks"

They judged the first version (the one that rhymes) to be more accurate than the second.

The name of this phenomenon is so, so apt. It's called the Eaton-Rosen phenomenon on Wikipedia.

The people who discovered this cognitive bias were not named Eaton or Rosen. These two people do not exist! Some wily user inserted this name on Wikipedia, and it stuck. Maybe because it's so rhythmic (try saying it aloud).

OK, we've come very far from the Chernobyl disaster, but I guess that's the lesson:

Beware of pretty ideas.

Just because something sounds simple, doesn't mean it's true.

Reality is complex. Sometimes it has simple explanations, and sometimes it's more complicated. Simplicity by itself doesn't tell you much.

It also helps to ask: "What am I motivated to believe?". Be wary of convenient explanations.

Before we continue, a quick note:

Did a friend forward you this email?

Hi, I’m Jitha. Every Sunday I share ONE key learning from my work in business development and with startups; and ONE (or more) golden nuggets. Subscribe (if you haven’t) and join nearly 1,400 others who read my newsletter every week (its free!) 👇

2. Golden Nugget of the week.

I spent a lot of time thinking about Seth Godin's blog post on The current and the wind.

Quoting it in its entirety (it's pretty short):

The wind gets all the attention. The wind howls and the wind gusts… But the wind is light.

The current, on the other hand is persistent and heavy.

On a river, it’s the current that will move the canoe far more than the wind will. But the wind distracts us.

Back on land, the current looks like the educational industrial complex, or the network effect or the ratchet of Moore’s Law and the cultural trends that last for decades. The current is our persistent systems of class and race and gender, and the powerful industrial economy. It can be overcome, but it takes focused effort.

On the other hand, the wind is the breaking news of the moment, the latest social media sensation and the thin layer of hype that surrounds us. It might be a useful distraction, but our real work lies in overcoming the current, or changing it.

It helps to see it first, and to ignore the wind when we can.

3. This blew my mind. 🤯

While everyone is going into rapture over DALL-E and GPT-3, Github's code-writing AI "Copilot" is now writing 40% of the code on the platform!

If you turn Copilot on, you’ll need to write only 60% of the code yourself!

4. Funniest thing I (re)watched this week. 🤣

That’s it for this week. Hope you enjoyed it.

As always, stay safe, healthy and sane, wherever you are.

I’ll see you next week.

Jitha