Sunday Reads #173: Intel, Hollywood, and what happens when you optimize for the short-term.

You've not thought about "time value of money" this way before.

Hey there!

And a special hello to my new friends who’ve joined in the last week. Great to have you here!

Hope you’re having a great weekend.

A bunch of you wrote in about last week’s article, Be careful what you set as your North Star. For it will consume you. So glad it gave you some food for thought 😊.

This week, let’s talk about Intel. You might not know it, but this once-dominant semiconductor behemoth is facing a “burning platform” situation.

1. What happens when the paranoid turn complacent.

I read a news article last week about Intel. Quoting from Intel Cuts Employee Pay to Maintain Quarterly Dividend:

Hot off the presses, we have confirmation from multiple employees that Intel is cutting costs tremendously at the expense of their employees. These cuts are broad-based, with employees having their compensation affected. Quarterly pay bonuses are gone, annual bonuses are being paused, 401k match is halved from 5% to 2.5%, merit-based raises are suspended, and there is a pay cut to all employees’ base salary based on grade.

All employees below Principal Engineer, grades 7 to 11, will get a 5% cut, 10% cuts will be instituted for VPs, and the executive leadership team will take a 15% cut, with Pat Gelsinger taking a 25% cut. These cuts hurt even more when we are in an inflationary environment. These cost cuts are, of course, dwarfed by their quarterly dividend, of course, which we have been clamoring for them to cut for over a year.

Intel’s leadership has decided that the dividend is more important than employee retention.

This is what Intel is saying, in essence:

Short term distribution of value is more important than long-term creation of value.

Intel is resting on its laurels. As for the future... well, it's the next CEO's problem.

A far cry from the paranoid Intel of the Andy Grove era, which used every crisis to become stronger and more dominant. He’d be turning in his grave right now.

This reminds me of something I wrote about way back in 2020: How would you discount your life?. It was ostensibly about time value of money and discounted cash flows, but was in fact about a lot more.

Discount rates and time horizons.

From the article:

I will not share a full intro to time value of money (Investopedia is a good resource). But suffice to say that it's a way of valuing future cash flows in terms of today's dollars.

How much is $10000 in one year worth to you today?

Keeping things simple, it's the amount of money you could put in a bank account today, that will return $10000 in one year.

If the bank pays 5% interest per year, then $9524 invested today will yield $10000 in one year.

That's what “time value of money” means: $10000 one year from now, is worth $9524 today.

In the same vein, any cash flow in the future will be worth less today. And the interest rate by which you discount it (5% in my example above) is the discount rate. This is, in a sense, the opportunity cost of that cash. What return you could have earned on the cash, if you got it today.

Cool?

Now let's do something a little more complex.

Assume you're getting a series of cash flows every year, growing at 5%. The chart below shows the proportion of the total value in today's dollars, that you get every year.

How do you read this graph?

Look at the curve for 6% discount (orange line). By year 10 (see X-axis), you've only received ~10% (Y-axis) of the total value of the cash flows.

But with a 20% discount rate (light blue line), you receive 75% of the total value (Y-axis) by year 10 (X-axis).

Now look at the 10% discount line. By Year 20 (last value on X-axis), you've received ~63% of the total value of the cash flows. What does that mean? It means that 37% of the total value accrues from cash flows beyond 20 years!

Three insights from the graph:

Insight #1: A dollar tomorrow is worth less than a dollar today.

That's why the value doesn't go up and to the right in a straight line; the curve flattens over time.

Insight #2: A majority of the value comes after Year 5.

Even with a 20% discount rate (which is exorbitantly high), 50% of the value comes after Year 5.

That’s an important principle: A huge chunk of the value of any investment - even at pretty high discount rates - comes several years in the future.

Insight #3: The higher the discount rate, the more important the short-term is vs. the long-term.

In the graph above, as we increase the discount rate, the more the initial years matter.

The converse is also true.

The more importance you explicitly place on the short term, the higher the implicit discount you're applying on the long-term.

In other words:

The time horizon makes the strategy.

Discounting the future at a low rate → Long time horizon → The future matters a LOT. Focus on exploration. Search for golden eggs.

Discounting the future at a high rate → Short time horizon → The future matters less. Focus on exploiting. Kill the Golden Goose.

And here's the thing: By observing the strategy, we can also infer the time horizon.

To adapt a popular Munger-ism: "Show me the strategy, and I'll show you the time horizon."

In the same article, I used Hollywood to illustrate this principle.

Hollywood and the Marvel Effect.

Between the 1970s and 1990s, the share of sequels was a small proportion of the movies released.

But from 2000 or so, it's been more sequels, remakes, and adaptations every year.

What happened in the 2000s?

Quoting from my article:

Among the ten highest-grossing movies of 1981, only two were sequels. In 1991, it was three. In 2001, it was five. And in 2011, eight of the top ten highest-grossing films were sequels. In fact, 2011 set a record for the greatest percentage of sequels among major studio releases.

Then 2012 immediately broke that record; the next year would break it again.

From a studio’s perspective, a sequel is a movie with a guaranteed fan base: a cash cow, a sure thing, an exploit.

And an overload of sure things signals a short-termist approach.

Remember: The strategy tells you the time horizon.

As Hollywood focused more and more on "sure things" in the short-term instead of creating new IP, it also signaled a belief about the long-term:

That the future doesn't look so rosy.

"Make your money now, because tomorrow you will not be able to."

And for what it's worth, in hindsight, they were 100% right! Streaming video has taken over, and fewer people are going to theaters (a trend which COVID has irreversibly accelerated).

When you fixate on the short term, you’re signaling extreme bearishness about the long-term.

With that in mind, let’s go back to our favorite semiconductor company.

Whither Intel?

Intel's time horizon is clear. The company is privileging short-term dividends over long-term profit, by a huge degree.

They’re signaling that cash flows to shareholders in Q1 2023 are far, far more important than the company’s profits over the next decades.

Remember the graph up top? Even at an exorbitant 20% discount rate, more than 50% of a company’s value comes from cash flows after Year 5.

So, by prioritizing immediate payouts and jeopardizing its long-term health, Intel is in effect putting a much higher discount rate on its future.

The message from the company is clear: Take your money, our future is not looking good.

There's a final question: How accurate is Intel's vision of its own future?

Dr. Maya Angelou said, in a very different context: “When people show you who they are, believe them the first time.”

In the same vein:

When people tell you their prospects are bleak, believe them the first time.

Further reading:

Intel Problems and Chips and Geopolitics from Ben Thompson are a good summary of Intel's predicament.

As he says, it's a canonical case of disruption.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) started by being "good enough". And over time, it became better than Intel. It's now manufacturing Apple's M1 Chip, AMD's chips (faster than Intel on desktop), and AWS' Graviton processor. While Intel is busy changing numbers on spreadsheets.

Post-script:

I wager that TSMC will announce a cut in its quarterly dividend next month, to recruit Intel's disgruntled employees. That would be a boss move.

Before we continue, a quick note:

Did a friend forward you this email?

Hi, I’m Jitha. Every Sunday I share ONE key learning from my work in business development and with startups; and ONE (or more) golden nuggets. Subscribe (if you haven’t) and join nearly 1,500 others who read my newsletter every week (its free!) 👇

PS. Next week I’ll write about Google’s existential crisis (I hope to get access to Bing’s Chatbot by then!). Subscribe now so you don’t miss it.

2. Golden Nugget of the Week.

You might be shaking your head at Intel's short-termism. But we regular humans are no different. In fact, we are worse.

Several studies (including the famed marshmallow test) have shown that we suck at waiting for future rewards.

This tendency is called hyperbolic discounting. Even more than Intel, we tend to focus on immediate gratification far, far more than on future rewards.

Richard Meadows gives a very visual example in his book, Optionality:

“That’s a problem for future Homer,” says America’s everyman, pouring a bottle of vodka into a tub of mayonnaise. “Man, I don’t envy that guy!”

This tendency to screw over your future self is called hyperbolic discounting. The value we place on a reward or punishment depends very much on when we’re going to experience it.

If we’re asked to make a decision that involves some trade-off taking place in the distant future, no problem—we’ll almost always take the option with the highest expected value.

But if it involves trading something off right now, we’ll often blow off the delayed reward and go for the short-term fix.

What's the lesson from this?

It's not that humans are stupid.

Rather, it is this: If you want people to take an action with long-term benefits, give them short term incentives too.

No matter how small or banal.

Free beer. Free donut. Cash. Anything.

If you want people to take action, you need to provide immediate value.

I remember an example from the early days of the COVID vaccine rollout. I mentioned this in How to hack the human mind (for a good cause):

The state of Ohio started pinning a lottery ticket to every vaccination card. And then this happened:

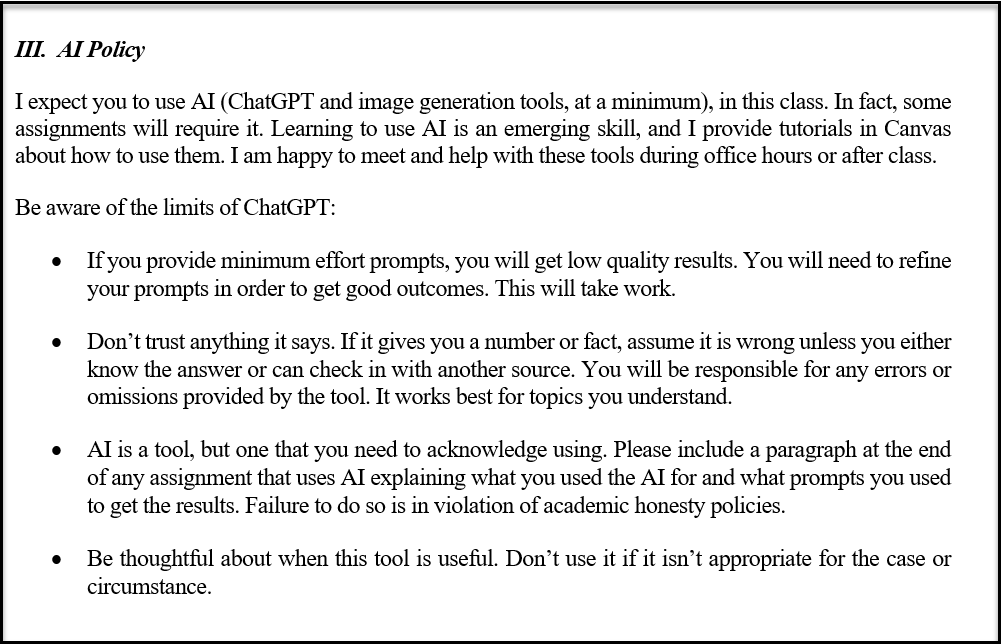

3. Simple rules for using ChatGPT.

Good advice from a Stanford professor:

Thanks to Varad Pande for sharing this with me.

4. I sure wish stress worked this way…

That’s it for this week. Hope you enjoyed it.

As always, stay safe, healthy and sane, wherever you are.

I’ll see you next week.

Jitha

[A quick request - if you liked today’s newsletter, I’d appreciate it very much if you could forward it to one other person who might find it useful 🙏].