Sunday Reads #189: What matters isn’t how often you’re right.

It’s what you do when you’re right.

Hey there! (and to recent subscribers, welcome!)

Hope you’re having a great weekend.

If you missed last week’s newsletter, here it is: How Microsoft became the world's most valuable company.

This week, let’s talk about inflection points. As an entrepreneur or CEO, what should you do when you see the world around you changing?

1. When you see a turning point, turn hard.

Better to risk boldness than triviality.

- Peter Thiel

I was reading about industry inflection points, in Liberty's excellent newsletter:

Consider one of my favorite industries, cable.

In the 1990s and 2000s, cable was mainly used to deliver video. Cable was a “meh” (though stable!) business; most of your revenue got eaten up by your suppliers (the ESPNs and ABCs of the world). And in a lot of markets you competed with satellite TV, who actually had a cost advantage as their larger (nationwide) scale let them negotiate better prices with suppliers...

That started to change in the late 2000s and early 2010s. Suddenly, cable was used more to provide broadband. Broadband is a much higher margin business than video...

In video, ESPN and ABC get a huge cut of every dollar, and there are no corresponding costs in broadband (the gross margin of providing broadband is ~95%; once the system is in place, you basically just need to pay for some electricity to deliver light down some fiber cables). Margins went way up!

Broadband is also a much “moat-ier” business than video; satellite had some real advantages when it came to video, but they were drawing dead to the superior infrastructure of cable when it came to the ever rising need for speed / capacity that broadband presented.

So you had a sudden change where cable’s margins went up substantially and the business got better as they suddenly leapfrogged a competitor…. and that’s not to mention that the video business didn’t just go away, so the broadband business didn’t just increase margins but it also accelerated growth.

So here you have a change that increases growth, increases free cash flow, and decreases competition intensity. That’s quite an inflection!

He then talked about John Malone, who started a new cable company focused on broadband, to take advantage of this exact inflection point.

And I was like, wait a second!

Isn't John Malone the guy who built a massive cable company in the 1980s, by taking advantage of tax loopholes?

Find a juicy pitch, and swing big.

The Outsiders is an excellent book about the skill of capital allocation. It's a must-read for anyone interested in business-building.

The author talks about the same John Malone, and his cable company TCI.

The details are beyond the scope of this article, but to summarize:

In the 1970s, John Malone realized three things about the cable business:

1: You can roll up cable operators and set up a flywheel of growth.

2: Cable is a high capex business. You need to build cable infrastructure as you expand. And you can use debt to fund this capex.

3: You can avoid paying taxes on your income, by taking debt and investing in capex.

The depreciation on this capex will reduce your profits, cutting your tax bill. But because depreciation isn’t really a cash expense, it will not affect your cash flows.

I had read about "depreciation tax shields" and "interest tax shields" in business school. But I'd never actually seen them employed with such brute force (and finesse)!

Malone exploited these three insights TO THE HILT.

He acquired 482 cable companies in 16 years, building a massive scaled powerhouse.

He invested hugely in capex, all funded through debt. In 1973, TCI's debt was 17x revenue.

He optimized completely to minimize taxes. A key source of capital at TCI was "Taxes not paid".

The result:

With all the depreciation and interest costs, his P&L showed losses for several continuous years. But his cash flow? It just kept growing and growing.

And as for his stock price...

Why am I telling you all this?

Because understanding an inflection point is one thing. But it's far more important to act decisively when you see it.

Let's talk about that, channeling Charlie Munger's wisdom along the way.

Mungerism #1 : Be fearful when others are greedy...

Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.

- Charlie Munger.

I wrote about Paytm in How much would you pay for a box that beeps?:

You all know the origin story of the success of Paytm, one of India’s leading payments providers.

When India did its demonetization back in 2016, Paytm swung. And swung big.

Front page ads in the country's premier newspapers welcoming the new digital economy. Thousands of foot soldiers recruiting retailers into the Paytm fold. The QR code at every store, stall, and hawker's cart.

Paytm saw a once-in-decades moment. A billion people being forced to move from cash to digital payments. And it swung for the fences.

I elaborated further in When the ball is in the zone, swing big. Using LVMH as an example:

LVMH is the world's biggest luxury company.

And the founder Bernard Arnault is the second-richest man in the world. Yes, richer than Bezos! With a net worth of over USD 150 Bn.

It all started with buying a bankrupt company for a single franc.

Mario Gabriele tells the story in LVMH: The Civil Savage:

Maison Dior had fallen on hard times. Founded in 1947, the couturier’s parent company slumped into the 1980s. That was less to do with the performance of Dior than the other businesses weighing down “Groupe Boussac,” including a flagging textile business and disposable diaper brand.

After declaring bankruptcy in 1984, the French government stepped in to find Boussac a buyer.

Arnault couldn’t believe it. One of the country’s most beloved and prestigious brands was for sale and at a discount! But even in its distressed state, buying Boussac looked beyond Arnault’s means. After all, the French government wanted someone who could commit to investing in the business. Though Ferinel (Arnault's family business) did well, the $15 million in annual revenue it brought in was still a far cry from the capital needed.

But Arnault was not to be deterred; he would get the money, one way or another.

His salvation came in the form of Antoine Bernheim, an investment banker at Lazard Frères...

In 1984, Arnault acquired Boussac for a token franc. The actual cost of the deal was $80 million, with Lazard financing over 80% of it. The rest came from the coffers of Ferinel.

Now, Arnault didn't just swing big in buying the acclaimed Maison Dior. He then slashed costs hard.

Mario continues:

He wasted little time in conforming Boussac to his vision. Despite promising to keep jobs and maintain the group’s structure, Arnault slashed aggressively, selling off unprofitable divisions and re-centering the business around Dior. With that streamlining went 9,000 jobs. The name changed, too, this time to Financiere Agache.

Whatever one thinks of Arnault’s gutting of Boussac, financially, it proved the right call. Over the following few years, Agache stabilized, then flourished. By 1987, the company earned $1.9 billion in revenue a year and netted $112 million.

Arnault could have stopped here. With a single franc, he had gotten himself an annual dividend of $112 million.

But he didn't stop.

He continued swinging big whenever he saw the opportunity. He saw a chance to own LVMH by playing both sides in a boardroom tussle, and he did it. More in Mario's article.

The rest of Arnault's story is more straightforward. A snowball inexorably transforming into an avalanche.

What did both these companies do?

Where others were fearful, they were decisive.

Mungerism #2 : Opportunity meeting the prepared mind.

Some of us have diamond hands, and ice-cold titanium flowing through our veins. Able to bet big, without worrying about the downside

The rest of us though? We need to train ourselves to see the opportunity when it arises. To see when the ball is in the zone, and get ready to swing.

I love this anecdote from The Power Law, about Bill Gurley and his investment in Uber:

Gurley’s investment in Uber was the perfect model of an intelligent Series A bet. Before joining Benchmark, he had been struck by the writings of Brian Arthur, a Stanford professor who studied network businesses. Companies that enjoyed network effects inverted a basic microeconomic law: rather than facing diminishing marginal returns, they faced increasing ones.

In most normal sectors, producers that supplied more of something would see prices fall: abundance meant cheapness. In network businesses, contrariwise, the consumer experience improved as the network expanded, so producers could charge extra for their products. Moreover, the improving consumer experience was matched by falling production costs because of the economies of scale in building a network.

As Benchmark had discovered when it had backed eBay, the rewards could be enormous...

After signing on with Benchmark, Gurley extended the eBay concept from products to services. His first hit was a startup called OpenTable, which connected diners to restaurants... What excited Gurley about OpenTable was that the network effects proved every bit as powerful as theory predicted: as more restaurants signed on, more diners visited the site, which in turn attracted more restaurants.

As Gurley and his partners pondered other sectors that might be ripe for similar treatment, they alighted on taxi and black-car services. There was so much inefficiency in pairing riders with drivers; surely better matching should be possible?…

In 2009, Gurley heard of Uber, which was looking for angel backers. To his delight, Uber’s strategy was to target unregulated black cars. “We’ve got to meet with these people immediately,” Gurley recalls thinking...

...Benchmark presented a term sheet to Kalanick, and after a bit of back-and-forth the partners led Uber’s Series A round, paying $12 million for one-fifth of the equity. Gurley had landed his OpenTable for black cars.

His ambition for the startup was that it might match OpenTable in its results, going public in due course at a valuation of perhaps $2 billion.

“Perhaps $2 billion”. Indeed. Even Gurley, with his prepared mind, didn’t realize how juicy this pitch was. But he seized it.

What matters in life isn’t how frequently one is “right” about outcomes, but how much one makes when one is right.

- Nassim Taleb, Skin in the Game

Which brings us to the last Mungerism.

Mungerism #3 : Opportunity doesn't come often, so seize it when it does.

I love this anecdote about George Soros and Stanley Druckenmiller from The Man Who Solved the Market:

Druckenmiller walked into Soros’s expansive midtown office to share his next big move: slowly expanding an existing wager against the British pound.

Druckenmiller told Soros that authorities in the country were bound to break from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism and allow the pound to fall in value, helping Britain emerge from recession. His stance was unpopular, Druckenmiller acknowledged, but he professed confidence the scenario would unfold.

Complete silence from Soros. Then, an expression of bewilderment.

Soros gave a look “like I was a moron,” Druckenmiller recalls. “That doesn’t make sense,” Soros told him.

Before Druckenmiller had a chance to defend his thesis, Soros cut him off.

“Trades like this only happen every twenty years or so,” Soros said.

He was imploring Druckenmiller to expand his bet.

The Quantum Fund sold short about $10 billion of the British currency. Rivals, learning what was happening or arriving at similar conclusions, were soon doing the same, pushing the pound lower while exerting pressure on British authorities.

On September 16, 1992, the government abandoned its efforts to prop up the pound, devaluing the currency by 20 percent, earning Druckenmiller and Soros more than $1 billion in just twenty-four hours.

Life-changing opportunities don’t show up often. When they do, you MUST swing big.

But the master of decisive action is a person you've likely never heard of: Henry Singleton.

Warren Buffett once said:

If you take the top 100 business school graduates and make a composite of their performance, their record will still not be as good as that of Singleton.

Lofty words from the Oracle of Omaha. Why did he say that?

Singleton was the CEO of Teledyne, a public conglomerate of the 1960s and 1970s. He saw two major inflection points, and he seized them like no one else did.

Inflection point #1: The Conglomerate Boom (1960s).

In the 60s, stock market investors loved conglomerates.

Conglomerates had higher Price to Earnings ratios than smaller companies. So they could just buy up companies, absorb their revenue, and command a higher stock price.

There was also less M&A competition, as private equity was still not a thing.

Singleton used his expensive stock (trading at P/E ratios of ~50) to buy smaller companies. Often at single digit P/E ratios.

And he didn't make 2-3 or even 20 acquisitions. He made 130 acquisitions during the boom. Profitable and growing companies. At dirt-cheap prices.

And then the market turned.

Inflection point #2: The Conglomerate Bust (1970s).

Starting in 1969, the public fell out of love with conglomerates. The P/E ratios started falling.

What did Singleton do? After a decade of breakneck M&A-driven growth, he abruptly threw the entire machine into reverse!

First, he immediately fired his entire M&A team. No more acquisitions.

Second, seeing how cheaply the public market was valuing his stock, he starting buying it back.

And he kept buying. Even as the P/E ratios kept crashing - and his stock kept getting cheaper - he kept buying it back.

By the end of it, he had bought back nearly 90% of the company's stock! i.e., he reduced the outstanding shares to 1/10th.

Which meant the Earnings per Share on outstanding shares skyrocketed.

The result: Through the boom and bust, Teledyne outperformed its peers nine-fold!

I started this article with Peter Thiel. Let me end with another Peter.

Once you decide, be decisive. Half measures are out of place.

- Peter Drucker

Before we continue, a quick note:

Did a friend forward you this email?

Hi, I’m Jitha. Every Sunday I share ONE key learning from my work in business development and with startups; and ONE (or more) golden nuggets. Subscribe (if you haven’t) and join 1,600+ others who read my newsletter every week (its free!) 👇

2. Fun Fact of the Week

I'm going for a concert this evening (Coldplay is in Singapore!). So let me share an interesting factoid about the music industry (from Trung Phan):

The Weeknd’s “Blinding Lights” is the most streamed song on Spotify ever.

Assuming the payout is $0.005 a stream, that song has paid out less ($18.2m) than the deal Harry and Meghan got paid to make 12 podcast episodes ($20m).

A little bit of a head-scratcher, isn't it?

How can the most streamed song EVER make less money than... a 12-episode podcast that only a fraction will tune in to?

The simple reason: They sit in different places on the P&L.

The difference between COGS and CAC.

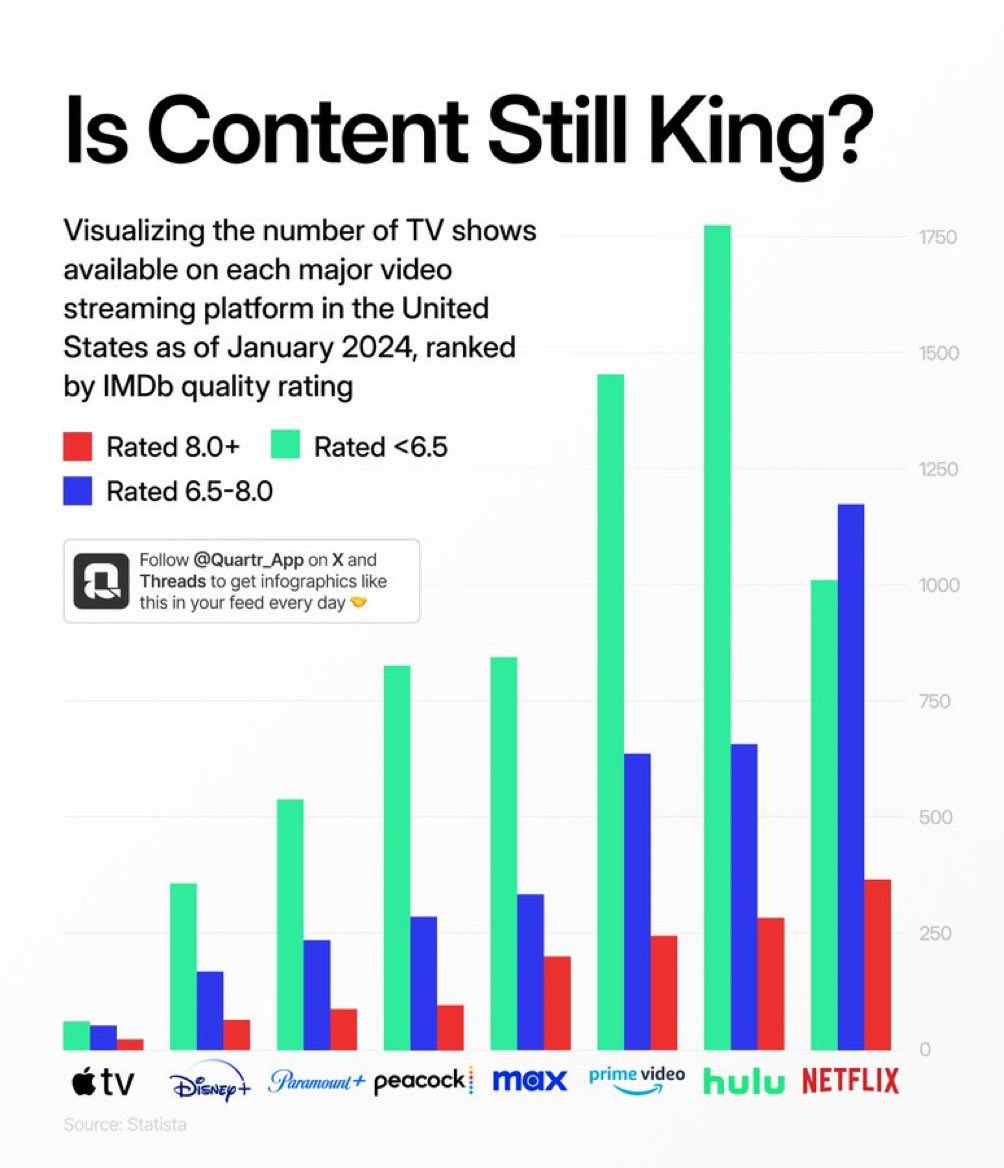

Tren Griffin tweeted an interesting chart last week:

Highly rated shows are a small minority across video platforms. The bulk of shows are quite average / bad.

As he said, Content is part CAC and part COGS.

You may subscribe to Netflix because of Stranger Things, but what do you watch the most? FUBAR, evidently.

In the same way:

The objective of the Harry-Meghan podcast is to bring new users to the platform.

It's a cost of acquiring new customers, or CAC.

If the podcast brings even 500K new listeners (and it will likely do more), then the cost per new user is $40.

Not that high, considering that many of these will convert to Spotify Pro at $10 per month.

It's a strategic investment, rather than an ongoing cost.

Whereas, payout to music artists is not bringing new listeners to the platform.

It's a variable cost that Spotify pays per listen. In that sense, it's Cost of Goods Sold, or COGS.

It needs to be a fraction of what Spotify makes from consumers on an ongoing basis. Much smaller.

Moral of the Story:

It doesn't matter what you're selling. It matters what your customer (Spotify in this case) is buying.

What job are they hiring you for?

Because remember:

"People don't buy quarter-inch nails. They buy quarter-inch holes".

3. "Daytime makes the infinity of the Universe go away" 😰.

This comic from xkcd is haunting.

Follow-up: Read Isaac Asimov's Nightfall (1941). It's a short novella, but one of his best works.

That’s it for this week. Hope you enjoyed it.

As always, stay safe, healthy and sane, wherever you are.

I’ll see you next week.

Jitha

[A quick request - if you liked today’s newsletter, I’d appreciate it very much if you could forward it to one other person who might find it useful 🙏].