Sunday Reads #159: 3 reasons angel investing doesn't work (and 3 secrets to do it right).

What I learned from my 18 investments and 3 "home runs".

Hey there!

Sorry I didn’t send the newsletter last week. I was struggling through the piece I’m sending today. I felt I needed a little more time to understand what I was trying to say 😄.

The topic is different from my usual. My articles are usually about becoming more effective as an entrepreneur or executive.

But today, I'll talk about angel investing.

1. The Metagame of Angel Investing.

I've been investing in seed / pre-seed stage startups for 5+ years now. It's through a fund my friends and I set up, called OperatorVC.

We’ve invested in 18 companies (all direct, not via platforms like AngelList) so far, with the following results:

One 10x exit (I really wanted to stay in, as long-time readers of this newsletter know)

Two 10x partial exits likely in next few months (I hope these will each eventually return the fund - i.e., 20x-30x return)

At least a couple more that might return at least 10x

3 have shut down 😞

My biggest reflection on this is - I've been so lucky!

Why do I think I'm lucky (versus, you know, an amazing investor)?

It's because there are structural problems with angel investing, which stack the deck against you.

Three problems, in fact.

Here's what we'll talk about today:

The three structural problems with angel investing.

Why then do we still invest? What motivates an angel investor.

My Angel Investing Model 2.0 - what I'm going to do differently going forward.

Let's get to it.

Three reasons angel investing doesn't work.

Reason #1: Are you getting paid for the uncertainty you're reducing?

OK that sounds like a mouthful. "Uncertainty you're reducing" - what the hell does that even mean?

Bear with me, it'll become clear in a minute.

Here's a graph from Bain about the startup fundraising lifecycle in India, 2000-2019.

Hmm, a few things jump out:

a. 92% of startups get no funding at all.

Of course, as Sid Betala pointed out on twitter, some of these startups might not be playing the venture game at all. They might be more steady state, "lifestyle businesses". Just because they didn't raise doesn't mean they failed.

But ignore that for now. It won't matter for this analysis.

b. Even after a seed round, only 23% raise any future round.

c. The probability of success (where success = raising a Series D or future rounds) goes up once you hit Series A, B, or C.

These seem interesting, but don’t really tell us something new.

Because this isn't the best way to look at these numbers.

Let's flip the graph.

Let's look at these same details, but as a funnel. 79,000 startups at the top, whittling down to 300 at Series C and 120 at Series D.

Now, this isn't to scale. But you can already see where the biggest drop off is: at the seed stage.

The seed investor is doing the most work - reducing the population of fundable startups from nearly 80,000 to 6,400.

But the core insight isn't jumping out yet.

So let's make this even more stark:

"To get one successful startup - that raises a Series D and beyond - how many startups do we need to see at each stage?"

It’s the same graph, but now the picture is clearer.

To get one success, a Series C investor needs to invest in only 2.5 companies.

This makes sense. The risk of failure should reduce substantially by then.

But even at Series A, you only need to invest in 13 startups. It's 5x the number at Series C, but still not that big. Seems par for the course - we all know that this is the deal.

OK, now look at the seed investor.

On the one hand, she has to invest in 53 startups to get one measly success. The probability of success is so much lower!

But far more important: she has to identify these 53 from a universe of nearly 700. That sounds like a lot of work!

And what work is she doing exactly?

She's reducing the uncertainty for the Series A investor.

She's telling the Series A investor, "Hey, you don't need to look at 700 startups to find one winner. I've already looked at them, and identified the 53 that are most likely to succeed. Here's the list. Enjoy."

Like the mama bird who pulls out the worms from the mass of gravel, so her babies don't have to search.

The unsung hero. Thanklessly toiling away in the background.

Ah, I can see an intuition starting to form.

Let's make it more concrete. Let's add 2 more columns: (a) probability of success, and (c) uncertainty reduction.

A startup's journey from impossible to inevitable.

Now it's clear! The seed / angel investor is doing the heavy lifting here.

Probability of success goes from 0.15% to 1.9%. Doesn’t sound like much, but that’s a 12x reduction in uncertainty. Or an increase of 12x in likelihood of success.

Yes, the job of the Series A-C investors is still tough. But it becomes trivially easy in comparison, once you give them a pre-vetted set of only the best startups.

Pre-vetted by the sleepless angel investor who's looking at startups 24/7.

Is she getting paid for this work?

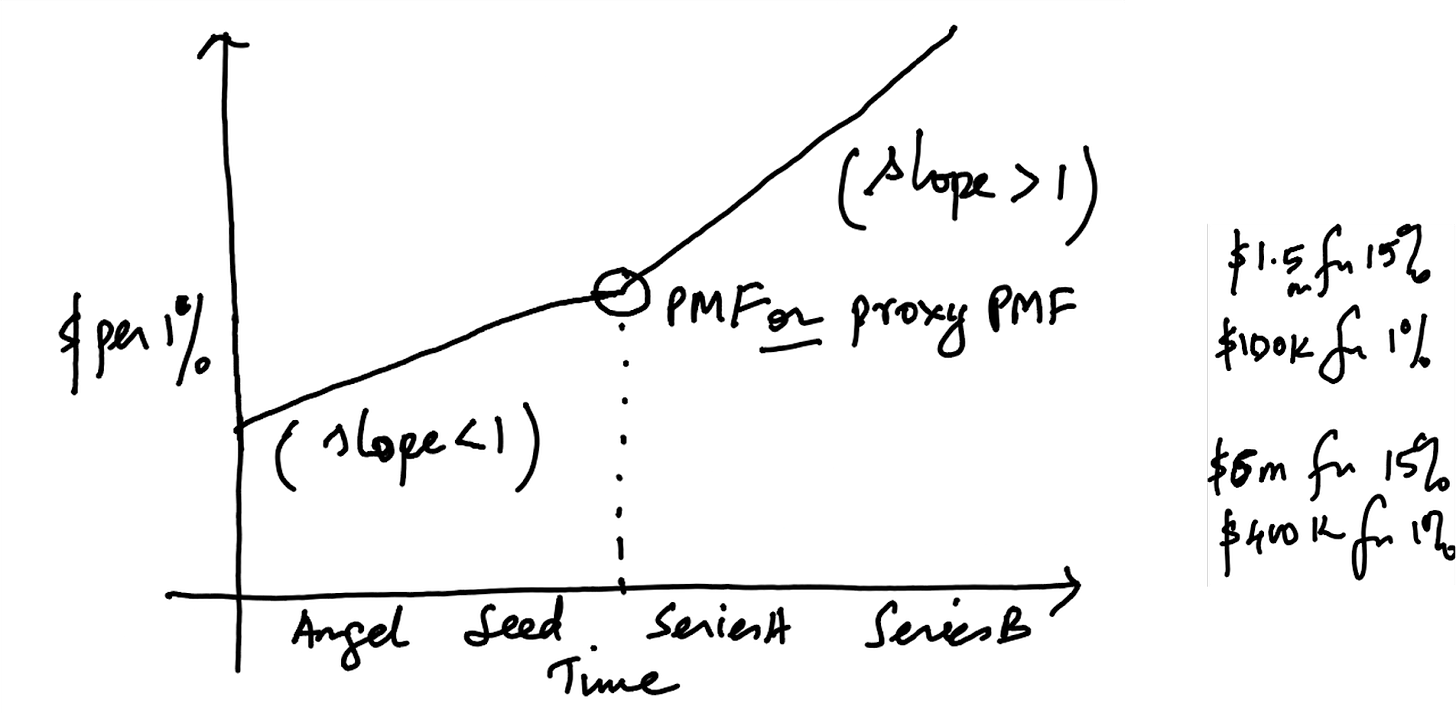

See this illustration, also from Sajith's article.

The valuation growth before Series A isn't that much. It only starts accelerating after Product-Market Fit (PMF), which is at Series A.

As Sajith said on twitter, the seed investor underwrites the journey of getting from MVP to PMF. That's the risk she's taking.

And she isn't getting paid enough for it.

The jury is out: Series A is the best stage to invest.

Mathematically speaking, most of the uncertainty is already reduced by Series A. And most of the valuation upside is yet to happen.

What's the magic that happens at Series A?

Series A is the best stage not because of its position in the funding lifecycle. It's because of its position in the startup's life cycle. i.e., when the startup has just found PMF. And is now ready to push the pedal on growth.

Let's put a pin on this point: the primacy of PMF for investing success. We'll come back to it later.

Reason #2: Access is the key driver of success.

As I've written in Exhaust fumes and infinite games - how startups are valued:

Coordination game + Power Law Distribution → Access is the biggest bottleneck.

We already know that VC investment is about "home runs". Many of your deals will go bust, but the ones that don't, should return big. i.e., a Power Law distribution.

...6% of deals produce 60% of returns, and 50% of investments lose money.

Long-term infinite game + power law → Everyone is really solving for access.

You don't win because of prescience about the future. You don't win due to an uncanny ability to pick winners. You don't win by building a tireless fundraising machine.

You win with access.

Persistent access to the best deals is the most critical leverage point in venture capital.

I also wrote about this in Drunkards and Streetlights:

The structure of angel investing works against all but a select few...

Even if you can reliably pick the winners with some degree of certainty, you’re still probably going to lose.

Because you probably can’t get into the winners. It almost always takes the right social connections to get into very early stage companies.

...only a certain type of person can truly be successful angel investing... they have the social clout to not get run over by VCs and literally pushed out of an investment.

…

Yes, the hardest part is finding the best companies.

Even if you're almost psychic at picking winners, you can only pick winners among the startups you see (i.e., under your streetlight).

And in a power law world (which the world of startups certainly is), one startup makes all the difference. What if it's one you just missed investing in? That one networking dinner you missed. That one week you were on holiday. The unicorn is just 5m away from your streetlight, but completely in the dark.

And it doesn't end there.

Reason #3: Your upside is often capped.

I've written about my experience with my first 10x investment, in the same article. Continuing:

And it doesn't end there. Even if you do find tomorrow's billion dollar company, so will other, bigger institutional investors. And they will have no remorse muscling you out, as Paige Craig found out with Airbnb.

But let’s say you clear this hurdle as well. Like Paige says, you "chase the deal until you're dead", and get an allocation. What happens then?

Congratulations. You get muscled out in the next big round.

This happened to me and OperatorVC. One of our startups hit a strong tailwind of growth, and we were super excited.

Guess what - we were forced to sell at 10x, because the bulge-bracket VC investing in their Series B wanted to "clear the cap table" as a precondition to invest.

Yes, 10x is not a bad return. But it's not good enough.

Given the number of failures you'll invariably see, you need your wins to be "home runs". You need them to be 30x, not 10x.

The 250x of legend is just that - a legend. A few angel investors have made it (and usually multiple times). But most get shunted out too early.

Imagine you're a baseball player. You get a lot of strikes, but the one time you connect sweetly and the ball is sailing to the stands... the umpire calls foul?!

What's the point of being in the home run business, if you're not allowed to hit home runs?

I mean, sure. You can figure out a way to not lose money. There's a rule-of-thumb that if you invest in at least 40 startups, then it's very unlikely you'll lose money.

But you want to win big, baby.

If your only aim is to not lose money, I dunno, put it in money market funds or something. (Or in ETFs, and you'll actually make some money too!)

OK, so what does this mean? That angel investing doesn't work?

Does this mean I won't angel-invest again?

No. I will continue. But I'll do it a little differently, to overcome these three structural issues.

And for any of you looking to start investing in startups, well - you can learn along with me!

But before we get into that - a short interlude on the psychology of angel investing.

Interlude: Why do we angel-invest in startups?

There's a book I borrowed from the local library last week: The Laws of Trading by Agustin Lebron.

The first Law is: Before you trade, know why you are trading.

At first glance this is trite. "I'm investing for profit, duh!"

But think again. Really - are you investing for profit?

Agustin gives the example of day-traders. Often, they're trading not to make money, but to create excitement in their humdrum lives.

Understanding this "Why" is important. Because in some cases, there may be better ways to get what you want.

If it's excitement you’re seeking, you can spend 20 dollars on a roller coaster ride. Instead of blowing up your life's savings on Gamestop.

In the same vein, here are some reasons I angel-invest, beyond just making money:

Exposure to new ideas: Talking to founders who are building exciting things.

Sense of community: Being part of an ecosystem.

Bragging rights: This could be, "My investee company raised a follow-on from Tiger Global and Sequoia". Or it could be, "I invested in the same round as Vijay Shekhar Sharma and Kunal Shah". For such brags, it almost doesn't matter whether you make money or not. You already feel like a winner.

Playing the lottery: A 30x is exciting! Far far more than a 10% long-term IRR in the public markets.

Now, once you're clear on the why, you can decide:

A. No, these reasons don't make sense. I only want to make money. So I'll buy ETFs instead. Bye bye, angel investing!

or

B. Yes, angel investing might not make me money, but it makes me happy. So I'll continue.

or the secret third option:

C. Now that I know my blind spots, I can still make money with angel investing. Let me show you how.

Angel Investing 2.0: Three things I'm going to do differently.

A. Solve for access - before anything else I do.

The most prescient vision for the future is useless, if you can't invest in the startups making that vision a reality.

So before anything else, solve for access.

Identify the best companies that have tailwinds:

(a) strong indefatigable founders...

(b) unlocking a surging reservoir of trapped value...

(c) with a disruptive new innovation.

And fight hard to invest in them.

B. Invest where I have an edge.

Invest in my circle of competence. Sectors that I know best (and that I know better than others).

Why?

Remember what we said earlier: The key driver to unlock the value of a startup is finding product-market fit.

In sectors I know better than others, I'll have the best chance of identifying PMF (or judging if it's close) before anyone else.

Edge = being able to identify PMF before anyone else.

C. Focus on supporting the founders.

Most angel investors are pure financial investors. It's ironic that they invest at the point when the founders need the most help - when the uncertainty is highest.

In fact, that's why we started OperatorVC. To support founders at this critical stage, with more than just our money.

Making sales connects

Brainstorming and testing the value prop and sales pitch

Giving product feedback

Doing interviews for senior roles

Helping raise capital

Whatever they need, we try to make it happen.

That's why we've been lucky with our investments. If you help the founder, he bats for you. When the Series B investor says, "OK, let's clear the cap table", he replies, "OK sure. But this angel stays on".

Now, I'm the first to admit: We've not done this nearly as consistently as we’d like.

But where we have, we've found our luck. It's luck, but it's not an accident.

I’m here to help, not to make money off an amazing founder.

Thanks to Satyaki and Bhaargav for the conversations we've had on this topic. And to Sajith and Ritesh for the discussion on twitter.

A few other footnotes:

1. The data I used is for India, but it applies to other markets too. Of course, the US market is much deeper - there are many more ways for startups to succeed, beyond the standard venture track.

2. If you’ve read this far, I’d love your feedback and thoughts on this. Just hit reply and let me know. I intend to edit this over time so it stays as my Angel Investing mission statement.

3. Further reading:

→ Sajith Pai's notes on Defining Product-Market fit

→ Tucker Max's Why I Stopped Angel Investing (And You Should Never Start)

👋 Did a friend forward you this email?

Hi, I’m Jitha. Every Sunday I share ONE key learning from my work in business development and with startups; and ONE (or more) golden nuggets. Subscribe (if you haven’t) and join 1,300+ others who read my newsletter every week (its free!) 👇

2. The most glorious thing I saw this month.

NASA shared images from the James Webb Telescope, and they are just amazing! You can check them out here.

Substack is warning me about my email length, so I won’t share them here. Make sure to see them at the link.

OK maybe I’ll share just one.

The name sounds like one of Elon’s kids, but the mind-blowing thing is this: Each of these pinpoints of light is a galaxy. And each of them is at least 4.6 billion light years away.

These images we’re seeing are from 4.6 billion years ago. And in some cases over 12 billion years ago. From the dawn of the universe.

Imagine someone in one of these galaxies training their powerful telescopes on the rest of the universe, much as we’re doing now. Would they even see the Milky Way, one of a gazillion galaxies in the universe? And what about us, orbiting one of a gazillion stars in the Milky Way?

Yes, each of us is important. But also inconsequential.

That’s it for this week. Hope you enjoyed it.

I finally got COVID for the first time this week, 2.5 years after the pandemic started. I’m on the mend, looking forward to being back to 100%.

Hope you’re staying healthy and sane, wherever you are.

I’ll see you next week.

Jitha